Light, Love - The Colors of Chagall

Photo from CBS News

We continue our exploration of modern artists with a look at Marc Chagall’s body of work. An outlier who eschewed the lauded art movements of his time, Chagall was pivotal in opening up modernism to a warm fluidity.

Marc Chagall’s lush and beautiful artworks swirl with a dreamy, heartfelt emotion. In his unique language of color and imagery he unapologetically expressed the joy, pain, and wonder of life. In this, he was totally avant garde. Cubism (with its unemotionally abstract aesthetic) was the reigning modern art movement of the era, and Chagall stood apart from it, rooted in his own voice, which was a blend of Jewish folklore, hometown memories, and his personal artistic style. From the time of his first show in Berlin before WWI, when he was still an unknown artist, people have been moved by the art of Marc Chagall.

Photo from MOMA

Photo from CBS News

Chagall said of his adored first wife Bella, “I had only to open the window of my room and blue air, love and flowers entered with her.”

Photo from Pinterest

This feeling permeates all of his artwork, and creates a sense of having left the space and time of waking life and entered a dream realm. In his scenes, people, animals, and houses often drift about, unbound by gravity’s pull. There is a softly curving feel, as if everything is swimming through the air, puffed by a wind, and people glide and sail, hang suspended overhead, and hover like cupids at the corners of the landscape. In his art nothing is static, everything slowly moves, and even body parts sometimes float and twist in fantastical fashion. In The Birthday, Chagall curves his head around in a total u-turn of the neck to meet the lips of his beloved Bella in a levitating kiss.

Photo from MOMA

He said, “ I myself do not understand them at all ... They are simply painted arrangements that force themselves on me ... The theories I could have made to explain myself, and those that others develop about me, are all nonsense.” Still, the significance of his work is deeply felt. Picasso, his contemporary and one-time friend said of him, “When Henri Matisse dies, Chagall will be the only painter left who understands what color really is. There’s never been anybody since Renoir who has the feeling for light that Chagall has.”

Photo from Studio International

Chagall was an interdisciplinary artist, and he explored various mediums throughout his life and career. His drawings illustrated the stories of Gogol, La Fontaine, and the Bible, and he made earthy ceramics painted in his signature style. His art has been made into tapestries by French weavers and mosaics by Italian stone layers, and his stained glass windows illuminate important political, religious, humanitarian, and cultural institutions.

Photo from mutualart.com

Photo via janekahan.com

Photo from studiointernational.com

As a Russian Jewish man, Chagall experienced anti-Semitism growing up and barely escaped the violence of Nazism in the second World War, but he disregarded the religious affiliations of his clients, choosing instead to focus on the possibility that his art might bring peace, contemplation, and a chance for reflection to all.

Photo from itravelwithart.com

His stained glass windows flood churches and synagogues alike with their rose reds and sky blues, and they hang in locations around the world, including in the Reims Cathedral in France (where 25 French kings have been crowned), the All Saints Church in England, the synagogue at Israel’s Hadassah Hospital, the Knesset–Israel’s Parliament, the headquarters of The United Nations, and the Art Institute of Chicago.

The mural he painted for the ceiling of The Paris Opera House elevates the otherwise heavily ornate space with its celestially light feeling, and his giant murals at the New York City Metropolitan Opera House inspire generations of New Yorkers who pass beneath them, including Jack Kerouac, who said, “Chagall painted the real world.”

Photo from Paris City Vision

Photo from the LA Times

Photo from mutalart.com

On walls, ceilings, and floors, Chagall’s art is transportive, but in the theater, his creations were physically brought to life. His first job in theater design was in 1920 for the State Jewish Chamber Theater in Moscow, where he created giant, colorful murals that decorated the space, presaging his later large scale works.

Photo from l’aventgardiste

He didn’t design for the theater again until he and Bella were living in New York City, twenty years later, as Jewish refugees of WWII. The company now known as the American Ballet Theatre invited Chagall to design the costumes and backdrops for their performance of Aleko, and the collaboration was a great success. The dreamy imagery of his painting style translated beautifully to the oversized backdrops.

Photo from Pinterest

Photo from artsy.net

Chagall’s handmade costumes were sometimes painted as the dancers wore them, so as to ensure the best possible placement of his designs. In a 1942 Hoy Magazine article he said, “ … we must take into account … that the stage light does not really illuminate the costumes … [they] have to have their own light … you have to know how to ‘paint it’.”

Photo from CBS News

Photo from Pinterest

The success of Aleko was followed in 1945 by a production of Igor Stravinksky’s The Firebird, for which he created handmade masks, headdresses, and sculpturally shaped bodies to clothe the whimsical, fantastical, animal-like people-creatures of the story.

Photo from LACMA

It was Chagall’s first major work after losing his wife Bella to a sudden illness, and the delicate, ethereal backdrops he made seem infused with her presence.

Photo from CBS News

Photo from LACMA

His final designs for the theater were for 1948’s Daphnis and Chloe at the Paris Opera Ballet, and the Metropolitan Opera’s production of The Magic Flute in 1967.

Photo from Art Now LA

Photo from LACMA

In his inimitable style Chagall beautifully captured the fantastic limits of the human experience. His otherworldly scenes were never abstract, they always maintained their sense of connection with feeling and emotion, and this warm approach to modern design is an inspiration today.

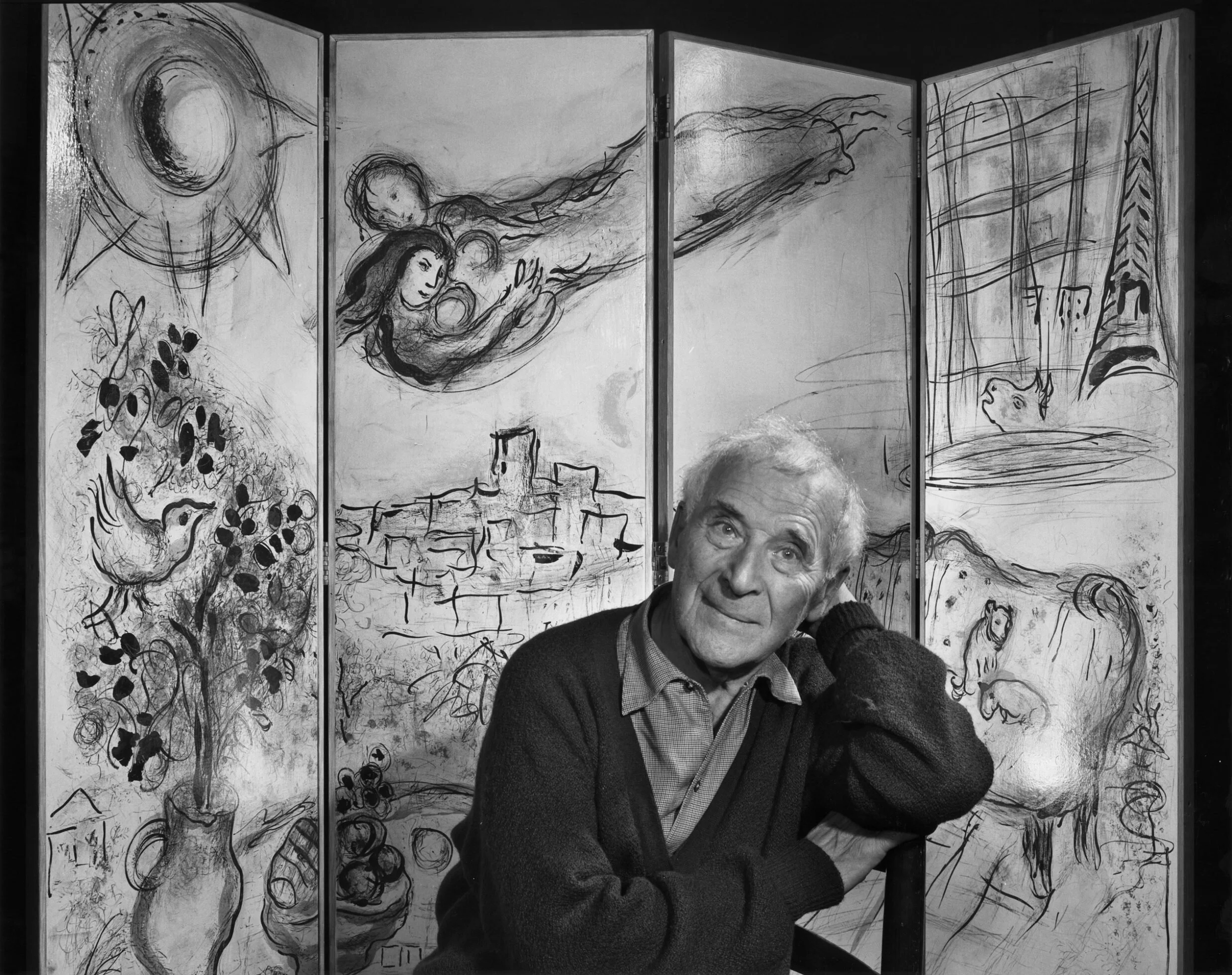

Photo from Yousuf Karsh

To explore his artworks more, take this video tour of the Marc Chagall National Museum in Nice, France.

Images courtesy of MOMA, LACMA, CBS, the LA Times, Yousuf Karsh, Artsy.net, L’Aventgardiste, Paris City Vision, itravelwithart.com, Pinterest, Art Now L.A., and Studio International.