Remembering Architect Harry Gesner - A Man Ahead of His Time

Photograph by Steven Lippman, Lisa Stoddard & the Gesner Archives via outerknown.com

Harry Gesner comes from a long line of inventors, adventurers, and artists, and his own life is an encapsulation of those all. He grew up in Santa Monica, surfed, skied, and downhill raced before any of these were mainstream sports, flew airplanes while still a teen, landed as a soldier on the beaches of Normandy during WWII (and nearly lost his legs there in battle), was a cartoonist in New York, turned down an offer to study with Frank Lloyd Wright, raided Ecuadorian tombs, married four times, designed Marlon Brando’s Tahitian island home (never built), and generally adventured his way through life, propelled by instinct and passion.

His father encouraged him to form his own ideas, outside of the insulated bubbles and echo chambers of academia, and from an early age, Gesner set out to make his own way and find his own voice. Outside of a brief time auditing Frank Lloyd Wright’s classes at Yale University, Gesner’s education in architecture took place on the job, apprenticing directly with craftspeople, including stonemasons, carpenters, electricians, bricklayers, and plumbers. He personally curated this education by selecting only the most exciting and exceptional projects to work on, and with the skills he picked up, and his uniquely singular vision, went on to very quickly, within a few years, establish a career as a modern architect. Even as he gained success and notoriety, Gesner would continue to work hands-on on his projects, “I can build a house from scratch because I know all the trades. It gives you more breadth and scope as to what can be done with the tools and materials at hand. And that, in turn, gives me the inspiration to test the limits…” (1)

Photograph from wallpaper.com

Photograph from wallpaper.com

Photograph from wallpaper.com

Gesner’s unique style blends architectural elements from Old World Europe, the handcrafted rusticness of Tolkien’s Middle Earth, and a sleek, boundaryless California modernism. His houses are both hefty and substantial, and weightless, arching skyward, and invariably, nature is involved. Glenn Cooper Jans, the original owner of Gesner’s Wave House said of the home, “It was as if we lived within, not apart from, the forces of nature, and surged with her changing moods.” (2)

Gesner’s interest in architecture began as a child, seeing houses being built on his paper route. Being an architect seemed like fun, and he started drawing and sketching his own designs. Decades before the trends of environmentally-friendly, sustainable, renewable, and green building, Gesner was creating in this way. He salvaged abandoned materials and gave them a new life in his own Sandcastle house, a beachfront Malibu property he designed and built for himself and his wife, Nan Martin. Old recovered telephone poles, repurposed marble slabs, and a high school gym floor were incorporated into the design.

Photograph from beach.film

The house celebrates Gesner’s love of the circular shape, which he admired for its inherent simplicity, efficiency, and strength. A cylindrical lighthouse style tower rises from the center of the rustic beach home, while the ground floor is a modern glass walled wheel of open plan living. An enormous brick fireplace with curving hearth anchors the interior, and rounded floor to ceiling glass window walls look out on the sea and sky. Wraparound wooden decks outside stand just above the sand.

Photograph from weddingestates.com

Photograph from beach.film

Photograph from beach.film

Photograph from beach.film

A lifelong surfer who surfed until he was 90 years old, Gesner found inspiration and spiritual connection in the water. Immersed in the elements during daily surf sessions, he cultivated a deep respect for the ever changing rhythms, inherent wildness, and ingenuity of nature. Allowing it to be his guide, he spent hours on each project site before starting to design, observing the light, wind, temperature, views, angles of sunrise and sunset, and textures of the terrain. As they’re slightly different for each project, so was each house unique. There was never any formula, just an intent to follow the contours of the earth and the inspiration of the moment. His designs perch on steep slopes and hillsides, nestle within canyons, and stand on the shore, close enough to the water to be washed in waves during ocean storms. Many of the sites he worked on were considered inhospitable and unbuildable, but he welcomed the challenge, “I am especially concentrating on the environment—and working with the environment, rather than trying to change it. Most of my houses are built on difficult sites. I demand it, almost, that they find the most difficult situations—a mountain, a rock, a lake—and then design for it. So that it looks like it’s a part of that world. Why destroy nature? It’s the most beautiful thing we have, so why not work with it?” (3)

In designing a beachfront property, he’d continue this process by also observing the site from the water. This was how he designed his iconic Wave House, one of his most acclaimed and well known designs. During a contemplative and insightful surf session, Gesner sketched ideas for the house directly onto his surfboard while bobbing in the ocean. This house sits just beyond his own Sandcastle home on the beach in Malibu, and has a striking design crowned with a trio of arcing roofs that appear as ocean waves paused just before they dip and fall, and curve into tubular barrels. The roof is covered in handcrafted round copper tiles, reminiscent of a fish’s scales.

Photograph from dwell.com

Photograph from Image Locations via housebeautiful.com

The iconic design of Gesner’s Wave House is said to have been the inspiration for the Sydney Opera House, which was designed by architect Jørn Utzon soon after.

Photograph from Budget Direct via NeoMam Studios & archdaily.com

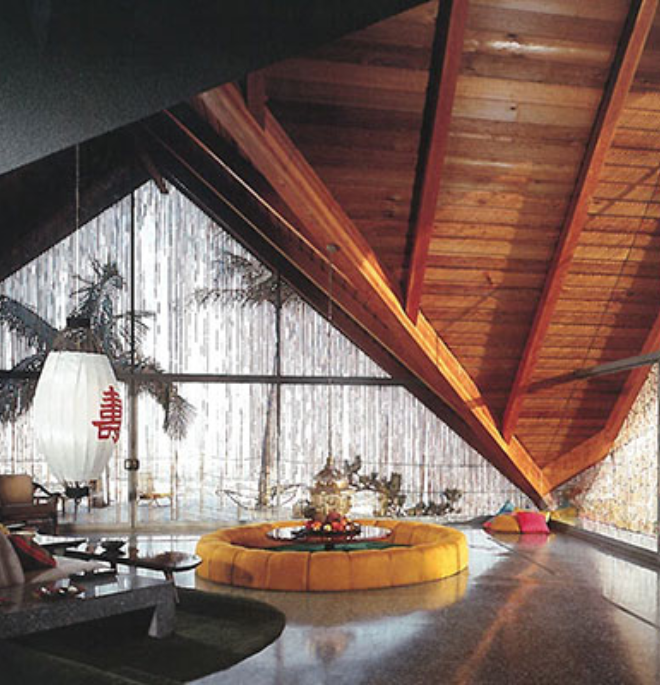

Gesner’s 1960s and 70s residential homes celebrated a James Bond aesthetic, and were designed for the entertaining lifestyle with sunken floors, indoor outdoor swimming pools, grotto landscaping, and eye-catching fire features. His Cole House, a Polynesian inspired Hollywood party home just above the Sunset Strip, built in 1958, originally featured double height beaded curtains that hung down the face of enormous glass window walls, and a swimming pool that could both reach indoors into the primary suite and shoot flames.

Photograph from iconichouses.org

Photograph from the May 25, 1959 issue of LIFE magazine via la.curbed.com

Photograph from The Oppenheim Group ogroup.com

Photograph by Kim Schneider, Tracy Clarke & Sotheby's International Realty via la.curbed.com

Photograph from la.curbed.com

Other iconic Los Angeles designs include:

The Hollywood Boathouses: Built by Norwegian ship builders in the late 1950s, this series of residential homes stand on stilts, floating out over the edge of steep and narrow hillside lots.

Photograph from Compass

Photograph from iconichouses.org

Photograph from tracydo.com

Photograph from Redfin via dirt.com

Photograph from la.curbed.com

Photograph from Redfin via dirt.com

The Eagle’s Watch: Built in 1955 in Malibu, but destroyed by fire in 1993. Gesner rebuilt the striking design in 1997 using concrete and reinforced steel.

Photograph from The Los Angeles Examiner via archive.curbed.com

Photograph via latimes.com

Photograph from airbnb.com

Photograph from airbnb.com

Photograph from wallpaper.com

The Encinal Beach House: Built in 1960, the house sits atop a rocky beach, not far from the Wave House and Gesner’s own Sandcastle in Malibu. The design features a stylized curving copper roof, warm wooden interior ceilings, and floor to ceiling glass walls in the main living area.

Photograph by Berlyn Photography via Beverly Higgins & Christopher Cortazzo of Coldwell Banker Malibu West via huffpost.com

Photograph by Berlyn Photography via Beverly Higgins & Christopher Cortazzo of Coldwell Banker Malibu West via huffpost.com

Photograph by Berlyn Photography via Beverly Higgins & Christopher Cortazzo of Coldwell Banker Malibu West via huffpost.com

Photograph by Berlyn Photography via Beverly Higgins & Christopher Cortazzo of Coldwell Banker Malibu West via huffpost.com

Photograph by Berlyn Photography via Beverly Higgins & Christopher Cortazzo of Coldwell Banker Malibu West via huffpost.com

Photograph by Berlyn Photography via Beverly Higgins & Christopher Cortazzo of Coldwell Banker Malibu West via huffpost.com

The Triangle House: Built in 1960 in Tarzana, the spacious open plan design sits amongst trees and hillsides. The triangle shape of the house is echoed in the guest house, a mini version that sits across the patio.

Photograph from Sotheby's via la.curbed.com

Photograph from toptenrealestatedeals.com via homestratosphere.com

Photograph from Sotheby's International Realty via sanfernandovalleyblog.blogspot.com

Photograph from la.curbed.com

The Stebel House: Built in 1961 in Mandeville Canyon, the house features surprising sharp angles in its gabled roofs, slanted walls, and windows, but is paired with a warm wood and brick interior.

Photograph from hous.com

Photograph from Redfin via dirt.com

Photograph from Redfin via dirt.com

Photograph from hous.com

Photograph from Redfin via dirt.com

The Scantlin House: Built in 1965 on property now owned by the Getty Museum (who also now own the house), the home features jetliner Los Angeles views, floor to ceiling glass walls, a swimming pool that becomes an indoor living room pond, and textured rock walls.

Photo from latimes.com via Pinterest

Photograph from flickr.com

Photograph from saladforpresident.com

The Flying Wing House: Built in the late 1970s in the Hollywood Hills, the house features soaring views, wooden ceilings, and exposed wooden pillars (the original client was the president of a lumber company who wanted to showcase his wares). The house was remodeled in 2014 by architect Dean Larkin.

Photograph by Noel Kleinman via dirt.com

Photograph by Noel Kleinman from The Oppenheim Group via latimes.com

Photograph by Noel Kleinman via dirt.com

Photograph by Noel Kleinman for The Oppenheim Group via robbreport.com

The Ravenseye House: Built in 1997 in Malibu, the house features triple height glass walls with cathedral-like peaked arches that frame ocean views.

Photograph from dwell.com

Photograph from priceypads.com

Photograph by Nathanael Williams via latimes.com

Photograph from Airbnb via therealdeal.com

Gesner’s drive, creativity, inventive mind, and abundance of ideas didn’t slow down in his later years, “I am more creative now than I was in my earlier years. Now, it’s mental, not physical.”(4) His later life projects included Houses that Survive: off-grid poured concrete and wood homes designed to withstand tornadoes, hurricanes, wildfires, termites, earthquakes, etc; Autonomous Tents: portable, low impact, semi-permanent structures that can be constructed or dismantled within days, requiring no foundation or leveling of land, and which can last 100 years, but can also leave without a trace (what he called Informal Architecture); the conversion of his 1957 silver 190 SL Mercedes convertible into an electric car; and the invention of a working municipal recycling system that turns waste into composted soil and then into ethanol fuel.

Photograph from dezeen.com

Photograph from dezeen.com

Photograph from dezeen.com

Photograph from surfersjournal.com

Gesner said he felt a part of the beauty around him when out in the ocean, and his homes are the same, extensions of their environment. They’re also reflections of him: celebrations of the wild and untamed Californian spirit. Harry Gesner passed away last month in Malibu, at the age of 97.

(1) - https://atlargemagazine.com/features/the-beach-boy/

(2) - https://atlargemagazine.com/features/the-beach-boy/